Ideas

A list of ideas and suggestions presented as part of my submission for the Master’s in Computational Arts at Goldsmiths College, London (see my end of year project, Recursus)

Subwords

Using letters as the basis for investigation, very much in the inspiration of the Oulipo and Georges Perec, one of the interesting constraint is to find words within words, that is,

nontrivial cases of inclusion, such as:

A ⊂ B: ‘love’ ⊂ ‘sloven’, ‘eat’ ⊂ ‘death’, ‘create’, which means finding a string within another string, possible now using wildcards in some dictionaries, but not on an extended scale, or using more refined criteria, such as a double search A ⊂ B and D ⊂ B, in this case ‘sloven’

containing both ‘love’ and ‘oven’, which could be useful when having two source words and searching for all words, if any, containing them both,

e.g. ‘love’ and ‘war’).

A + B = C: that is the recipe for many natural compounds, e.g. airplane, pitchfork, etc., however it is possible to conceive nontrivial situations, e.g. a word C that can be cut in half, each one meaning something, even if that division hasn’t got anything to do with actual grammar or etymology, such as ‘Hamburger’, German for ‘[sandwich] from Hamburg’, which was cut into ‘ham’ + ‘burger’, producing the new word ‘burger’ that has enjoyed its infamous destiny ever since … Computationally it might be trickier to produce, as one must parse a vocabulary list finding words who display two, or more, existing subsets (‘errant’ can be read as ‘err’ + ‘ant’).

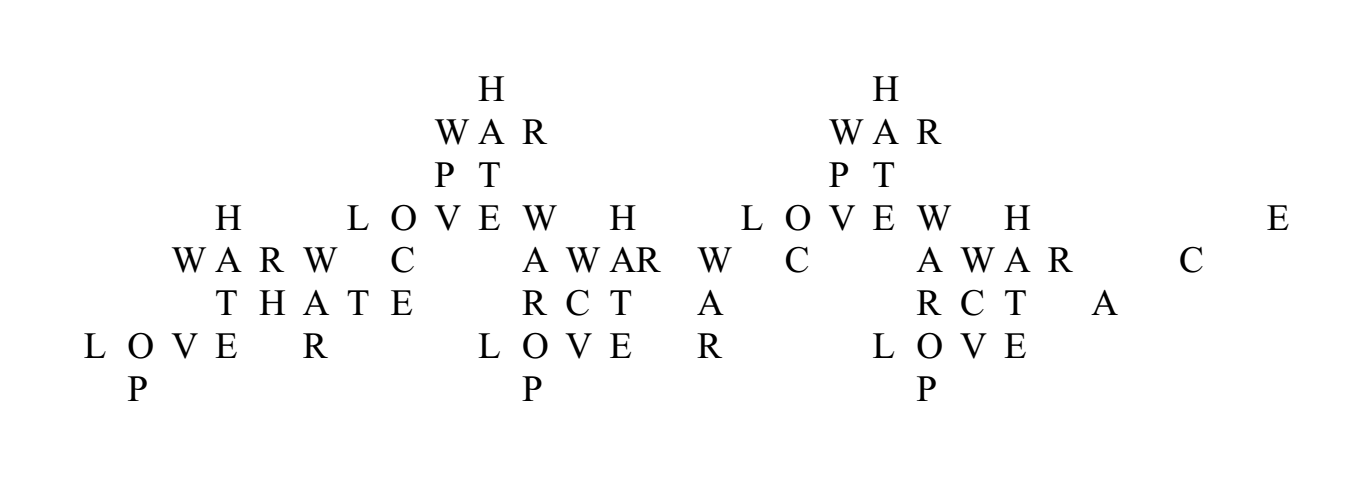

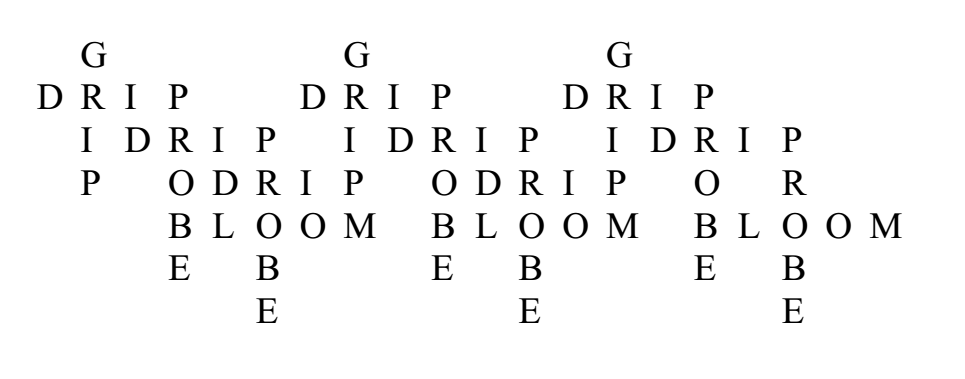

A ∪ B = C: the constraint is looser here, the order of the letters within the subwords having to come up in order, but the two or more subwords being allowed to be ‘interwoven’ (example: Eve ∪ war = weaver):

W A R

E V E

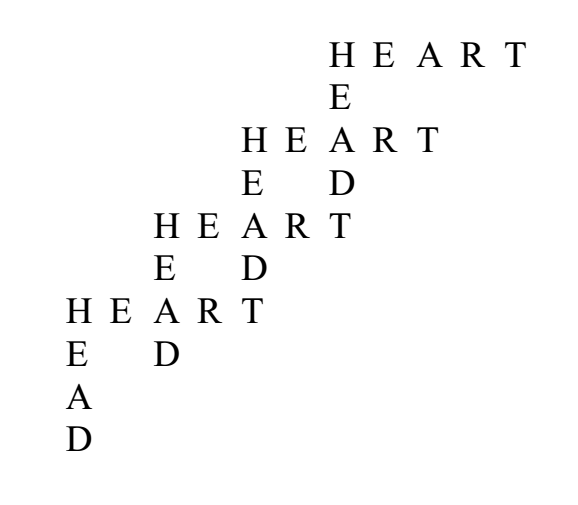

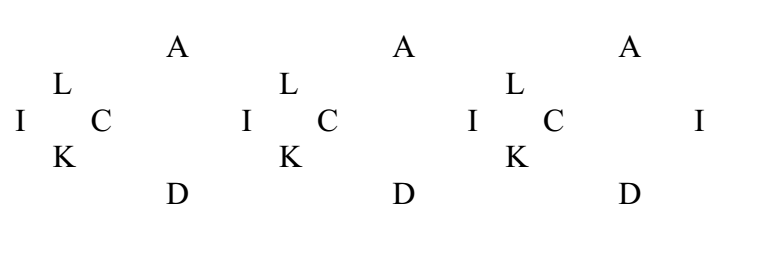

A ∩ B, or ‘siamese words’: in this case one does not even require the union of the subwords to be complete in either ways (no ‘superword’ C is required, and neither is it that all the letters of each words are used). This case creates, not unlike rhyming, a way of linking two words, using some of their letters, with the amount or placement of the letters being left to aesthetic research. The third example has the common letters forming an independent word, which could be a subcategory of this genre (two words that both contain the subword X can be linked in this way, and one can think of more complex situations):

W K

E A

H D

O E

B S O L T E

A U

C R E

E A T

D H

After developing techniques for words, it might be interesting to expand those to phrases and sentences. Just as some pictures show two possible interpretations (Freud and the lady), one could have a string of letters creating two possible sentences. In all this, mastery of the computer could greatly enhance the ability to find nontrivial and beautiful possibilites. The programming challenge would be to devise a specific kind of ‘advanced search’ not yet provided anywhere to my knowledge, such as, ‘find words that are composed of two, three, or more existing words’, with options such as ‘subword must be a string’, ‘subwords can be interwoven, but the letters must appear in the right order’, etc.

§

Swaps

THE MOVING TEXT (An Oulipian homage to Jean Tinguely)

Drawing inspiration from the techniques of the Oulipo, Jean Tinguely’s injection of movement into abstract paintings, the GIF format (examples here, here, hereand here), the following pieces would explore the possibilities opened by the digital text.

Program a computer to find the possible sets of words (three 3-lettered words, four 4-lettered words, five 5-lettered words, etc.) allowing for the following linear display (on an LED display with as many slots as there are letters):

ABCD BCDA CDAB DABC ABCD etc.

The challenge being that each combination should be a word, and, even, that the sequence of words might either straightforwardly mean something, or be evocative, beautiful or powerful in a literary way. Once the computer has found all the possibilities from a given vocabulary database, the task is to choose the ones deemed of value. An interactive version could be a display where a, say, four letters form a word, and a user can touch each letter to change it. The computer has in store all the possibilities of letter-swap leading to another word, and this for all possible words composed of four letters and accessible from the first one displayed.

L O

V E if touched in the upper left-hand corner, could become

R O

V E if touched in the bottom left-hand corner, could become

R O

L E etc.

☙

WOOL

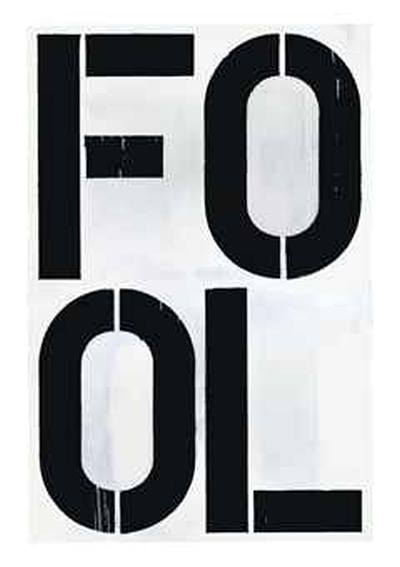

Christopher Wool produced various works based on words and letters. Among those, ‘Untitled’ (1990):

Liking the idea and visual result, but slightly frustrated by the simplicity of his linguistic/literary approach, I decide to attempt a work that would expand on key features of the work, as well as injecting a new technological dimension. Using the double ‘O’ as the basis for the visual balance of the work, a word search is conducted in the OED (“?oo?”), giving the following results (rarer or obsolete words preceded by an asterisk): boob, booh, book, bool, boom, boon, boor, boot, cook, cool, *coom, coon, coop, coot, *doob, *dook, *dool, doom, door, food, fool, foot, good, goof, *goog, *gook, *gool, *goom, goon, goop, *goor, hood, hoof, hook, *hoon, hoop, hoot, *jook, *joom, kook, *loob, *loof, look, lool, loom, loon, loop, *loor, loot, mood, *mool, moon, *moop, moor, moot, nook, noon, *noop, *noov, *pood, poof, pooh, pook, pool, poon, poop, poor, *poot, *rood, roof, rook, *rool, room, *roon, *roop, root, *sook, *sool, soon, *soop, *soor, soot, took, *toom, toon, toot, voom, *voor, wood, woof, wool, *woon, *woop, woot, *yoof, *yoop, zoom, *zoon, *zoot. Using this list, it is possible to produce a new, dynamic, animated work, which would switch between various words, while the two ‘O’s remain. One could imagine a random process that would 1) pick which word to display next; 2) how long said word would remain, 3) what probability to assign to each individual word (or, perhaps, in a simpler way, simply a lower probability for asterisked words, and a standard one for the rest).

☙

LATTICE

On the basis of a similar vocabulary database and one word chosen by the user, the computer displays and spatialises the possibilities generated by the simple rule: ‘you may change one letter’.

Example (done manually using the OED and wildcards, excluding obsolete forms):

LOVE

{cove, dove, gove, hove, rove}

{lave, live}

{lobe, lode, loke, lone, lope, lore, lose, lowe}

{Ø}

CUNT

{bunt, dunt, hunt, lunt, munt, punt, runt}

{cant, cent}

{cult, curt}

{Ø}

Remains to determine what would be the best way to display the result.

An idea could be, for a 4-lettered word at least, to attribute each letter a direction on the plane (up, down, left, right), and use that part of the plane to display the results, either in the form of trees (8 branches up, 2 branches left, 2 right), or more randomly, in the form of wordclouds.

N.B.: One could envisage an algorithmic reproduction of the process, whereby each new result becomes the start of a new generation, rapidly creating proliferating patches of text. In this case the mother word could be the biggest, with each generation getting smaller (either branches, like roots, getting ever thinner around each word, or ever smaller word clouds…). Since each generation would have among its possibilities a return to the step, a complete sequence would be fractal in nature, and could lead to interesting visual effects.

☙

PATHS

Using the same constraint as above, one can think of a more linear application: from one word one may jump to another changing but one letter, thus creating paths. Each of the steps must be an existing word, and the whole must display literary/poetic interest or beauty. Conversely, one could give the computer two words and it would return all the possible paths between the two, the work being to pick the ones that are nontrivial or of artistic interest.

§

Solids

(See this page)

Having as its starting point an axiomatic conflagration of Plato ‘s cosmological philosophy (in the Timaeus) and the array and extremes of human desire (the most easily accessible forms of which being internet shock videos involving extreme sexuality and violence, which were one of the source of inspiration for the piece),Solids, a collaboration with composer Remmy Canedo, is an attempt to draw a bridge between the apparent chaos of human perversion and on of the most fundamental philosophical texts from the tradition aiming at finding a method for deciphering the world through the lens of mathematical structures. Plato ‘s method of classifying the fundamental elements of the world (fire, air, water, earth and aether, which he inherits from earlier figures) using mathematical solids is used as a lens through which it is possible not only to apprehend various sexual perversions (scatophilia, zoophilia, rape, sometimes leading to mutilation or murder, etc.) as material, but also providing a formal framework out of which it is possible to ultimately turn them into structured literary production. Thus, the various solids (tetrahedron, hexahedron, octahedron, dodecahedron, icosahedron) offer a constraint not only at a thematic level (“if one were to classify perversions into five categories, which ones would these be?”), but also at a literary level (“how can writing be developed in five different ways to accomodate each perversion?”, or “given that a particular perversion has as its figure a solid with twelve faces, what are the consequences for texts written about it, if it is to be projected on such a figure?”).

Among various forays into the possibilities at hand using Plato’s framework, one came up that is particularly suited for computerization: starting with a rather simple premise, that given a general ‘theme’ specific to each solid, it possible to have one relevant word on each face. A tetrahedron is then a set of four words, a hexahedron, a set of six, etc. This is already sufficient a level of constraint for an attempt: how to find the best four, or six, words, that create a poetic and powerful set? However, two constraints may be added to that which could then, given the sheer difficulty of finding appropriate sets, give computational search power a good enough raison d’être: first, one may restrict the number of letters of each word to the number of faces of the solid, to increase coherence (four-lettered words for the tetrahedron, etc.); second, one could create a true letter puzzle by requiring that each letter be associated with an edge, and that the ‘other side’ of the edge, on the adjacent face, have the same letter attached to it. In the latter option, the gradual covering up of each face with a word would add letter constraints to the other faces, leading to the last face being entirely determined when all the others are complete. If one wishes the word set to be non-random, and, ideally, interesting, on a literary level, and given that it is almost impossible to execute this task in any way but empirically (starting with one word on one face, then going for a second face, each time checking that the letter constraint is being respected), the most efficient scenario would be to have a computer program produce possibilities generated from a comprehensive word list (e.g. the OED) and the rules and then among them separate the wheat from the chaff.

§

Advanced Logometorology

Wordclouds today are prefabricated and corny. Skills in programming could allow for truly crafted shapes but also, perhaps more importantly,

a full control over the fine-tuning of the process, so as to be able to remove words that are irrelevant (‘the’, ‘is’, etc.), or reverse the size/frequency ratio, so as to show the unique words instead of the most frequent, and, perhaps expand the technique so as to have the computer parse the text looking for phrases instead of single words, or other requests.An interesting development could also be to create wordclouds that update themselves often, so as to reflect, for instance, the state of a discussion (a hashtag) at any given point around a specific topic.

The wordcloud would then be in motion, adapting to the frequency of words at any point. For such use, advanced skills in display (3D?) would be useful.

A quite big project around this would be to have an animation showing the evolution of the English language as recorded by the OED: the computer would have to search into the database for the earliest dates a word is recorded (and latest, for obsolete ones) and display them all in a huge cloud that would evolve as new words appear and old ones become obsolete. If it were possible to add to that the frequency tools found in Google,

one could then have an index for the size of each word in the cloud (this latter option would only be English since 1800).

§

CAL Tools (Computer-Assisted Literature)

Computer-Assisted Translation has become the standard for professionals worldwide, but we are still to witness such a turn within literature itself: most of its tenets, however, could be extended to literary practice, especially when it comes to working with memories, terminology databases, and other tools allowing for extended and specific types of searches (synonyms, words of a certain length for verse, etc). Develop a program that has the ability to study one’s own literary (or academic, etc.) production, in order for the writer to become more aware of its own stylistic tendencies and habits. The program could for instance display not only the frequency of words but also of certain phrases and, perhaps, certain syntactic constructions. The goal would be to make them conscious to the mind of the writer so as it can then choose whether it wants to use them, or on the contrary seek to diversify its style.

§

Kakekotoba

A kakekotoba(掛詞) or pivot word is a rhetorical device used in the Japanese poetic form waka. This trope uses the phonetic reading of a grouping of kanji (Chinese characters) to suggest several interpretations: first on the literal level (e.g. 松, matsu, meaning “pine tree”), then on subsidiary homophonic levels (e.g. 待つ, matsu, meaning “to wait”).

The Japanese kakekotoba can taken to be the literary equivalent to musical modulation: two systems (tonalities, semantic fields in a text) have a common element, which is used as a juncture between them. In the first universe (first tonality, first part of the text), said word (or chord) means something, in the second, it means something different, and because it is placed in the middle of the two, it contains the two layers at the same time (this can be also be viewed as the literary equivalent of optical illusions, Freud and the lady again). The kakekotoba is based on homophones, but it might be possible to find other possibilities of exploration, for instance strings of letters producing various words, or several words together readable in more than one way. The latter option opens to a more developed stage, where an entire phrase/sentence acts an ambiguous element connecting two parts of a text.

§

Recursions

One of the ways in which puns can be produced is algorithmic in its nature: adding layers of meaning, usually only one, but sometimes more, as in many cases of word-formation in the late James Joyce, by inserting one or more words into another serving as a basis, or by intertwining two together (and then keep adding). Consider the following examples:

vocabulary

+ tentacular

→ vocatentaculary

+ concatenate

→ voconcatentaculary

+ tempt

→ voconcatemptaculary

+ ocular

→ voconcatemptoculary

vocabulary

+ globular

→ vocaglobulary

+ global, balbutiate

→ vocaglobalbulary

→ vocaglobalbutiate

→ vocaglobalbutiary

The basic pattern is to seek words that have common subsets (substrings)

of letters, finding the appropriate combination, and then start again.

It is possible to envisage a computer program that would either produce puns on its own, or, perhaps, that would enhance human pun production by searching for and displaying possibilities that the user could choose from.

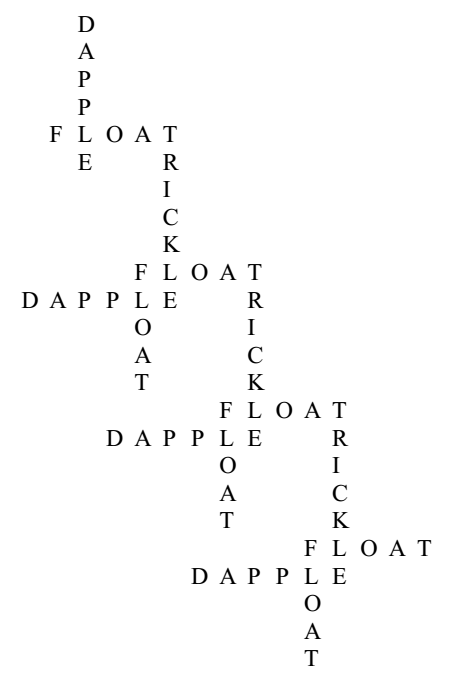

A not dissimilar phenomenon occurs on a syntactic level. Hyperhypotaxis,

the ‘excessive’ insersion of subordinate clauses within a sentence, is a formal tool that can be used literarily for various ends. In this case,

it is less clear how computers could help produce such sentences,

however, there could be alleyways for nontrivial visualisation: imagine one would like to write a short text, of the nature of the prose poem,

consisting only of this one, very complex sentense, with the formal wish of increasing syntactical complexity. The end result, in the context of a traditional book, could be a paragraph on one or more pages, the syntax of which having to be decoded by “that ideal reader suffering from an ideal insomnia”.

However, one could imagine ways of graphically translate syntactical intricacies: were the text laid out on one line (see thisfor instance), one could assign to each subordinate clause a -1 in height, and perhaps a +1/2 for parenthetical elements, producing a cascade-shape representation.

§

Tilings

Spatialisation of words (and letters) using geometric patterns, for instance Arabic geometric patterns as an inspiration.

Fractalscould also be another interesting point of departure, as well as lesser-known mathematical structures such as Penrose tilings, for which one would need to find an appropriate method that could produce the ‘non-periodic’ word/letter set that could adequately be projected onto it.

§

Brainstorming

Patrick Tresset developed robots that draw what they see. Is it possible to get robots to listen to our brains (through electrodes?) and write down what we think?

§

Tourettify!

Program a robot in order to produce (if possible real-time) besmirching of colloquial speech, drawing inspiration from the blurts of violence or obscenity arising from the Tourette syndrome. The user’s voice is recorded and transformed in the following ways:

- insertion of profanity and insults within the discourse (and one could think of original ones, created for that purpose; or taken from external sources, like Shakespeare, Tintin, Hip-hop and pop-culture in general);

- translation of the message into radically offensive and/or vulgar speech;

A piece could be concieved where participants are invited to sit in separate booths and coverse with each other, each utterance being filtered and modified by the computer. Each participant only hears the other’s modified voice, not the modified result of itself speaking. The two participants could experience skillfuly crafted verbal abuse in an interactive context. One could also devise the opposite mechanism, whereby utterances are softened and made more loving and caring, and see if that would lead to participants liking each other more.